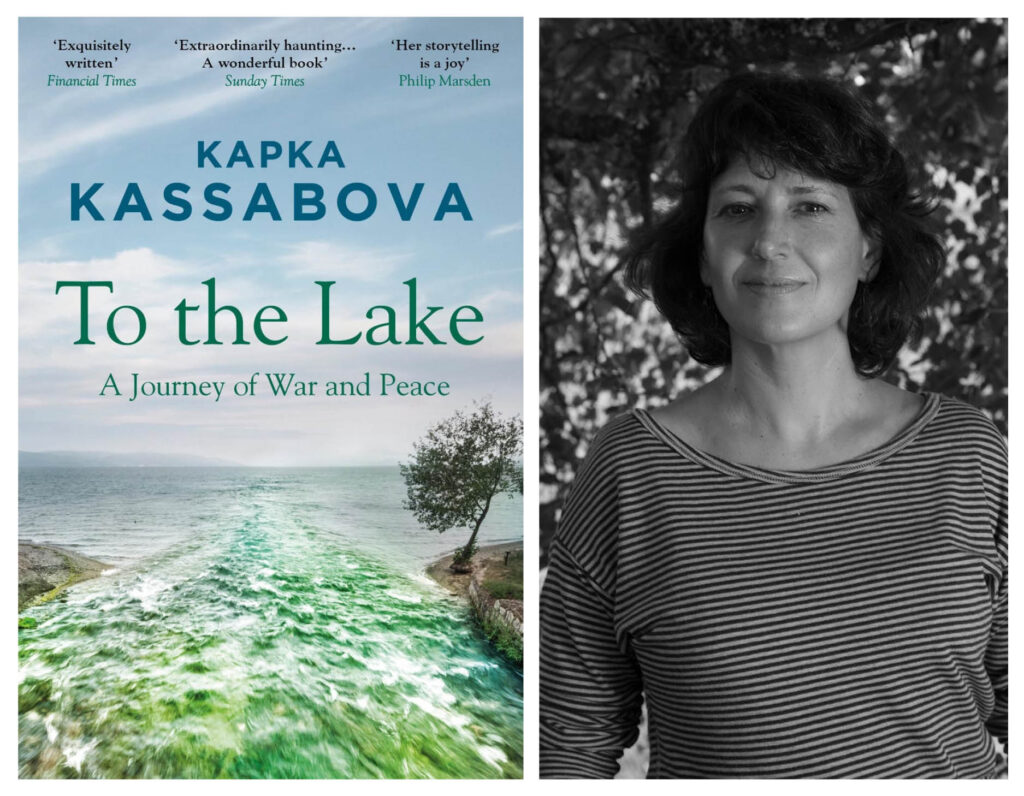

To The Lake: A Journey of War and Peace by Kapka Kassabova, published by Granta, has been shortlisted for the 2020 Highland Book Prize.

To The Lake: A Journey of War and Peace by Kapka Kassabova, published by Granta (memoir, reportage, travel).

Lake Ohrid and Lake Prespa. Two vast lakes joined by underground rivers. Two lakes that have played a central role in Kapka Kassabova’s maternal family.

As she journeys to her grandmother’s place of origin, Kassabova encounters a civilizational crossroads. The Lakes are set within the mountainous borderlands of North Macedonia, Albania and Greece, and crowned by the old Roman road, the via Egnatia. Once a trading and spiritual nexus of the southern Balkans, it remains one of Eurasia’s oldest surviving religious melting pots. With their remote rock churches, changeable currents, and large population of migratory birds, the Lakes live in their own time.

By exploring the stories of dwellers past and present, Kassabova uncovers the human history shaped by the Lakes. Soon, her journey unfolds to a deeper enquiry into how geography and politics imprint themselves upon families and nations, and confronts her with questions about human suffering and the capacity for change.

Kapka Kassabova is a poet, novelist and writer of narrative non-fiction. Her acclaimed memoirs Street Without a Name (2008) and Twelve Minutes of Love (2011) were followed by Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe (2017) which won the British Academy’s Al-Rodhan Prize for Global Cultural Understanding, the Saltire Scottish Book of the Year, the Edward Stanford-Dolman Travel Book of the Year, and the inaugural Highlands Book Prize. It was short-listed for the Baillie-Gifford Prize.

Visit : kapka-kassabova.net

An excerpt from To The Lake: A Journey of War and Peace by Kapka Kassabova, (Granta 2020)

Across the Lake

It was early morning and the water was transparent like a

membrane, newly born. My guide was a young woman called

Ivanka who happened to be a cousin of Tino, my cousin and

Tatjana’s son. I had booked the boat trip without knowing this –

yet again, I had landed in the lap of distant relatives.

The faces of the gated town had begun to feel too familiar after

a week. There were streets I had started to avoid, and I was keen

to get out on the water. The eastern shore in particular interested

I wanted to find out how my great-grandfather had escaped

in 1929 by making the lake crossing myself. Had he crossed the

whole length of the lake to the Albanian shore in the south? He

had been with a friend. In the era before the motorboat, they

would have rowed thirty kilometres.

‘Anything’s possible if you’re desperate enough,’ said Ivanka’s

dad in answer to my question. He was a placid man with kind

eyes, and the boat was his. I asked him if he remembered my aunt

Tatjana, his sister-in-law.

‘How can I not?’ he said simply, and wanted to say more, much

more, but couldn’t find the words. Besides, I was a stranger to

him. ‘Tino grew up with us, after her death.’

His own girls had set up the first hiking tour company in

Ohrid.

‘Dad encouraged us all the way,’ said Ivanka, and unfolded a

camping table. We breakfasted on succulent tomatoes, sheep’s

feta, burek (stuffed pastry), and triple drams of ‘breakfast rakia’

made from grapes – golden and smooth, only forty per cent, said

the dad.

‘When my sister and I trained as mountain rangers, we

were the only girls out of a hundred!’ Ivanka said. ‘They hadn’t

expected women so we had to do the same press-ups as the men.

But we did it. Dad always believed in us.’

Dad was not one to take credit, but he did his bit for the business,

with the boat. Of course, the business was family-run. If you

were to succeed at anything here, you did it as a family.

‘It’s a super-conservative culture,’ Ivanka said. ‘My sister and I

are exceptions – doing something active, daring to dream, not just

marry and have kids.’ Getting out on the lake with the wind in

your hair helped you dream, I felt it already.

We passed the forested peninsula of Goritsa, once Tito’s

summer estate. It was still the property of the president of the

republic, occasionally in use.

‘We went in to see the villa, once,’ said Ivanka. ‘It’s like a

museum. Tito’s portraits are still on the wall. Creepy.’

The few shore miles after that were lined with aged Yugoslavera

hotels whose names provided a chronological rewind of the

country’s self-image, from Communism back to antiquity: ‘the

Granite’, ‘the Cement’, ‘the Metropol’, ‘the Philip of Macedon’,

‘the Dessaretae’. Above them perched the Lake’s monasteries.

The most mysteriously named among them was St Stefan Panzir

of ‘the Chain Mail’, after an army of soldiers in chain mail who

perished on that spot just south of the Egnatian Way. But who

were they? Nobody knew for certain.

One reasonable guess, based on oral histories, is that the battle

foreshadowed the First Crusade and the rising tide of bellicosity

in Western Christendom against the East. The Islamic East and

the Christian East, both. The Normans invaded Albania from the

Adriatic during the years 1080–85, and were defeated here by the

Byzantines, the then defenders of Lychnidos, whose archbishop

had taken refuge with hermits in the cliffs. And what made the

Byzantine army so strong? The huge numbers of Turkic mercenaries

and other Orientals and ‘barbarians’ in its ranks.

The more I learned about this region, the more it struck me

that the south-west Balkans, and the Balkan peninsula as a whole,

were an arena both of marriage and of war not only between

Christianity, Islam and Judaism, but also between the Occident

and the Orient, and therein lay their complexity and their

trouble. The Orient had given birth to Judaism, Christianity,

Islam, Hinduism; and before that, the earliest practices of Asian

Shamanism. It was in the Orient’s nature to contain all of these

simultaneously, across time: to be polyglot. Not so with the

Occident, or not to such an extent.

We learn from the medieval epic La Chanson de Roland and

also from Al Idrisi’s Book of Roger (twelfth century), that the Byzantine

army had soldiers of twenty-seven ethnicities and faiths,

including Turks, Persians, assorted Slavs, Armenians, Pechenegs,

Avars, Hungarians, and ‘Strymonians’ (from the region of the

River Struma, or Strymonas). As late as the end of the thirteenth

century, when the armies of Charles of Anjou continued to assault

the peninsula via the Egnatian Way, Byzantium and Bulgaria

repelled them with the help of Turkic and other Asiatic soldiers. It

was the ambiguous, many-faced, multi-theistic East pitted against

the more singular righteousness of the West – and against one

another, as in the case of Bulgaria and Byzantium. These internal

Christian wars ultimately opened the way for the Ottoman Turks

to enter the European stage.

I looked at Ivanka and her dad, all three of us born of this

peninsula’s baggy, natural cosmopolitanism, understanding each

other perfectly, yet artificially estranged from each other by divisive

internal politics.

We rejoined a wild coast. As the hotels disappeared, the limestone

mountain grew. I could see the odd hermit niche, and even a rope

ladder hanging halfway down the cliff. It had been a while since

anyone had climbed there. Perhaps Gotse Zhura had been the last.

‘In the distant past, the lake was higher,’ said the dad.

Some of the caves now out of reach could have been reached

by boat even just a hundred and fifty years ago. If we went far

enough back in time, the lake would become a sea. Geological

relics of its existence have been found as far as the Debar Lake,

sixty kilometres to the north. It had been one giant body of water,

inside the Dessaret basin, a tectonic depression formed three to

five million years ago. It gave me vertigo to think that the time

we have been here (forty-six thousand years for humans, less for

sapiens) is but a blink in the life of the lake. And here I was, trying

to understand the emotional life of just a hundred lacustrine

years.

I asked how deep it was where we were.

‘If you can see through, then it’s no more than twenty-three

metres,’ the dad said.

The reason for this extreme transparency is the multitude

of sublacustic springs that feed the lake, including the ones that

come all the way from Prespa.

‘This lake is Europe’s largest natural reservoir of clean water,’ said

Ivanka. ‘The greatest threats are pollution and over-urbanisation.’

A natural scientist told me that the lake’s retention period,

meaning the time it takes to fully renew its water, is seventy-five

to eighty years. That’s a lifetime! It was almost a miracle that the

lake had retained its cleanliness, clean enough to drink, when all

else around it – the state, the economy, the climate – had been

eroding. The engine was too noisy for us to talk, so Ivanka and

I lay on the hard boat benches and soaked in the morning sun,

while her dad steered us south. The lake sparkled, full of sky.

But the jagged tops of the mountain, where a white paraglider

hovered like an albatross, looked hostile to humans. I was sure that

Kosta had done this crossing by night. He had been one of countless

lake escapees between the two world wars.

‘Many didn’t make it,’ the dad said. ‘They were eaten by the

fish.’

‘Or the samovilas tricked them to the middle of the lake,’ said

Ivanka, smiling.

‘We have no business in the middle of the lake,’ the dad said,

not smiling.

One of the lake’s folk legends involved the Slavic vila or samovila,

the shape-shifting entity that takes the form of a woman,

like a nymph who moves very quickly above ground and usually

appears at full moon, in forests and other liminal time–spaces. I’d

never before heard of lake nymphs, though.

‘This lake has its own samovilas,’ said Ivanka. ‘They sing to the

fishermen, songs without words. Until they drown.’