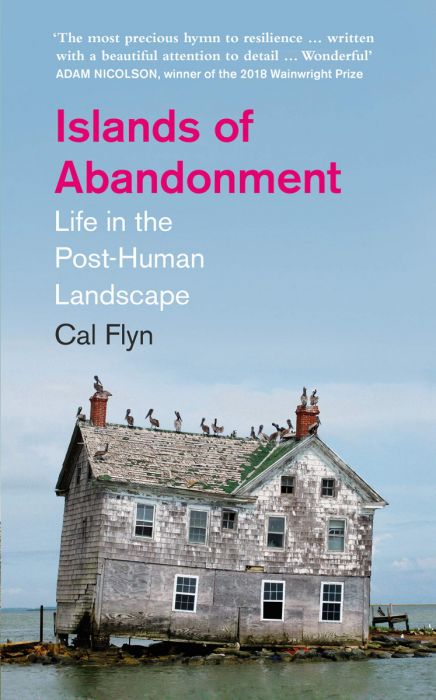

This book explores the extraordinary places where humans no longer live – or survive in tiny, precarious numbers – to give us a possible glimpse of what happens when mankind’s impact on nature is forced to stop. From Tanzanian mountains to the volcanic Caribbean, the forbidden areas of France to the mining regions of Scotland, Flyn brings together some of the most desolate, eerie, ravaged and polluted areas in the world – and shows how, against all odds, they offer our best opportunities for environmental recovery.

You can read a short extract from Islands of Abandonment below.

Cal Flyn is a writer from the Highlands of Scotland. She writes literary nonfiction and long-form journalism. Her first book, Thicker Than Water, about frontier violence in colonial Australia, was a Times book of the year. Her second book, Islands of Abandonment—about the ecology and psychology of abandoned places has been shortlisted for a number of prizes including the Wainwright Prize for writing on global conservation, the British Academy Book Prize and the Baillie Gifford Prize for nonfiction. Cal’s journalistic writing has been published in Granta, The Sunday Times Magazine, Telegraph Magazine, The Economist and others. She is the deputy editor of literary recommendations site Five Books, and a regular contributor to The Guardian. Cal was previously writer-in-residence at Gladstone’s Library and at the Jan Michalski Foundation in Switzerland. She was made a MacDowell fellow in 2019, and was recently announced as the 2021 Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year.

Excerpt from Islands of Abandonment

The following excerpt, taken from the chapter ‘Swona’, is published with permission from Cal Flyn and William Collins and should not be downloaded, distributed, or reproduced in any way.

The sun sets and rises, sets and rises, chasing shadows across the floor, across the table, across the wall. Rain lashes the windows to one side, salt spray the other. Days pass.Weeks pass. Months. Years.

Outside, torrents rush past the rocky shore. The light- house to the south and the beacon to the north pulse out automated advertisements to their presence. Constellations whirl overhead. The moon waxes, wanes, waxes, wanes, waxes. The cattle live, give birth, and die.

Inside Rose Cottage, dust settles unseen. At first it forms a thin veneer, but then a thicker, felt-like scrim, pulled up and over everything. It forms over tea towels hung to dry over a stove long ago gone out. It settles on the coal in the scuttle and the kitchen table sitting ready for a meal, with a jar of marmalade, tinned milk powder and a box of biscuits at its centre. It settles on the papers stacked in piles on the sideboard, and on the sewing machine packed neatly in its box, on the ham radio by the window and the stopped clock on the mantelpiece reading ten minutes past three.

Later, as the damp sets in, the air grows thick with decay. Tins pox and swell in the cupboard where they were stockpiled. Glassware takes on an opacity – that hazy, milky quality of age – and the mirror a patina of grey-green that creeps in from the edges, clouding the reflection. Salt in the shaker solidifies into a single, moulded block. Upstairs the beds are still made, ready to be slept in, the sheets pulled neatly up and tucked in tight.

Just over a decade after the Rosies’ departure, the photographer John S. Findlay came to document the island, and noted that the sense of human presence was still so strong as to prompt him to knock upon every door before he entered. The feeling that the owner was only in the next room, or shortly to return and catch him, was intense. At that time, the house still resided in a realm of mere absence – as if someone had slipped out for a walk – although a few artefacts suggested the start of the transmutation of this absence into something altogether more profound.

By the time I enter the house, more than three decades later, the metamorphosis has advanced. Now, it has clearly been abandoned for some time. There are still traces of how things were left – the wipe-clean tablecloth left in place, though its laminae are separating, its skirts shred- ding onto the floor; the soft furnishings rotting away to bare wooden frames; paperwork stacked, but soaked and softening to pulp – but the next phase, ruination, is now surely close at hand.

A newspaper rests on the table – wet and flimsy and folded in half. Its uppermost pages are too perished to be readable; when I tentatively lift its corner with one finger I find the cover hiding inside: a Press and Journal, bearing news of a change in government: Ted Heath out, Harold Wilson in.

I carry in my phone a photo of this room, taken by Findlay in 1985, and I bring it up now to chart the advance of its decay. What strikes me instead are the other ways in which the scene has changed. Items are missing: that stopped clock, for one thing, with an art print propped up in its place. The doors to the cabinet have been flung open, the paperwork rifled through and stuffed back. A kettle – aged, rusted – has appeared on the stove top. Though many years have passed, the suggestion of unseen presences moving in the space between the photo and the scene before me is uncanny.

A tide of mud has swept in under the door and across the floor. It has settled in a layer of around an inch in depth, soft and wet still, perhaps from the storm that’s just passed over – the one I had to wait out in a tent on South Ronaldsay for two days, canvas flapping through the night, the whole setup threatening to take off. In the mud ,a broom lies half-submerged and dropping its bristles. And next to that, a set of footprints which are not mine.

These too catch me unawares. I feel a sudden chill. I freeze where I stand and peer through a loose lattice of floorboards into the bedroom above, then down again to the footprints. It’s not clear how long they have been there. It’s sheltered inside the cottage, with the door tied shut. They could have been here for years, like footprints on the moon. Although – they look fresh.

I speak out loud without meaning to: ‘Hello?’

No answer. The house presses in silently against me.