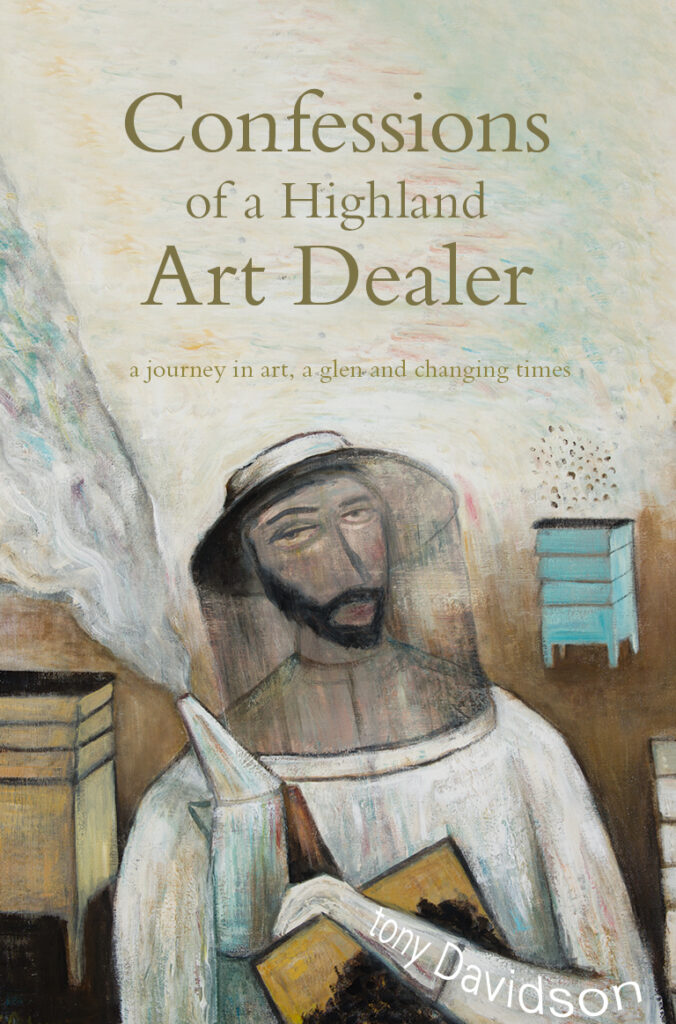

This is the story of a young, ambitious art dealer who transformed an unused rural church in Inverness-shire into one of the country’s top commercial art galleries. It begins with the enigmatic Black Allan opening the door of an abandoned kirk in rural Inverness-shire and follows with its shoestring-budget adaption to a new life, and it ends with an environmental call for change – a call for awakening.

Along the way, as Tony grows the gallery, we travel across Scotland and are introduced to the rarely seen world of Scottish artists. It suggests the purpose and beauty of what they do, and shows, with brilliant storytelling, one way to survive quarter of a century of rapid change.

Woodwose Books, 2022

Tony Davidson was born in 1967 in Edinburgh, moved to the Highlands in his twenties and opened the doors of Kilmorack Gallery in 1997. He has been writing about artists since then, looking for new ways to express what they do, and constantly reinventing the gallery to reflect our changing times. ‘Confessions of a Highland Art Dealer’ is his first book.

You can read a short extract from the book below

Extract from Confessions of a Highland Art Dealer

The following excerpt is published with permission from Tony Davidson and Woodwose Books and should not be downloaded, distributed, or reproduced in any way.

After the three-hour trip to Glasgow, Tatyana sits me on a black fabric-covered box. She glides in small steps, her feet hidden beneath a tent-like dress. Her voice is syruped with Russian.

‘I vill now svitch the lights off and begin the performance. I will geev you the full show. The works are old and fragile, so I do not do this often,’ she tells me. ‘Eet is rare. Enjoy.’

It is dark. A light comes on. With a rattle, the first machine comes to life. This is his self-portrait as an organ-grinder.

Bang.

A mechanical foot stamps a rhythm while a thin metal arm slowly turns a mangle and a song begins. It is a slow Russian lament. Two eyes set within a face of burr and bison move from side to side and a mouth opens and closes. Below this, on a pendulum, rides a monkey, swinging on the organ-grinder’s balls. Maybe it is the sad Russian voice in the background, or the stamp of the foot, or the slow fatality of the movement but I find tears in my eyes. This woodwose is the keeper of many dreams. One by one the machines tell the organ-grinder’s stories. In the top-down world of Leningrad, where Bersudsky lived until he moved to Scotland in the 1990s, life was harsh. A nightmare about Stalin’s purges is told, as well as the loss of a poet friend and the building of Babylonian towers. Rats are in control while all that is left is birth, sex and death. As one machine finishes, another lights up and I shuffle around the darkened room. Automata belong to the realm of dreams. They are the muted other that bring messages from places flesh can’t go. There is nothing like this anywhere in the world and I have just seen the complete show alone in the dark.

The lights switch on and I return to the present. I am in a large windowless room with black screens, lights and the mechanical sculptures. Off this big room is Eduard’s workshop and a kitchen. Bersudsky says nothing as he offers a cigarette. They are a long, strong brand. He picks up a bottle of vodka and gestures an offer of that too. Tatyana explains. ‘Eduard pretends that he does not speak English, but we all think he does. He just doesn’t like words.’

Like my days of living in the gallery, socks, T-shirts and jeans hang from radiators. Other evidence of habitation is hidden from view in boxes. Eduard and Tatyana’s life is not in Russia or Scotland, it is in this room, in the dream-machines that Eduard makes and the theatrical productions that Tatyana creates from them. I drive north with a few wooden carvings and a raven that swings its head and tolls a bell when a button is pressed.

‘We use it as a doorbell,’ Tatyana offers.